From each hand-sewn napkin to every item off their locally-sourced menu, a house-turned-restaurant called Cabel inside the Malacaňang presidential complex in Manila highlights the specialities from major Philippine islands, capturing the soul of the Filipino culture through decadent food, service, and interior design.

“We want to take pride in the fact that each major island has so much to offer,” said King Cabel-Moreno, the owner of Cabel. “Often places in Manila focus on the main dishes like adobo, pancit, and lumpia, but why not allow people to have a taste of everything from north to south? Our islands have too much to share to not show our diversity.”

The Cabel-Moreno family took over the restaurant after the pandemic forced business to cease in 2020. It used to be called Casa Roces, which was the 1940s heritage house of the Roces family who established and own The Manila Times, the first English-indigenous newspaper of the country.

To pay homage to the family’s legacy, a statue of a newspaper boy holding a copy of The Manila Times stands tall greeting each guest as they enter the restaurant. But the adulation of the Roces family does not

stop there, as Moreno kept the same layout, architecture, and sourcing of food and materials in hopes of respecting and appreciating those that came before him.

“The Manila Times was, and somewhat still is, one of the only chances for us to really have a voice,” Moreno said. “That means a lot for us, who have been here for so long. So we want to respect that as much as we can through keeping their traditions and history alive.”

Moreno weaves his own family history into the showcase of Filipi

no heritage throughout the restaurant. Shelves are lined with family pictures, each room is named after a member of Moreno’s family, and paintings of his mother and siblings are displayed above the main dining tables.

Sourcing locally, the dining room features rattan chairs, colorful Machucan floor tiles, and sliding doors printed with old editions of The Manila Times. The tablecloths and napkins are both hand-sewn by a family from Sulu, with colorful illustrations of traditional aspects of Filipino culture, including fiesta, taho, and the Maglalatik, or “coconut dance.”

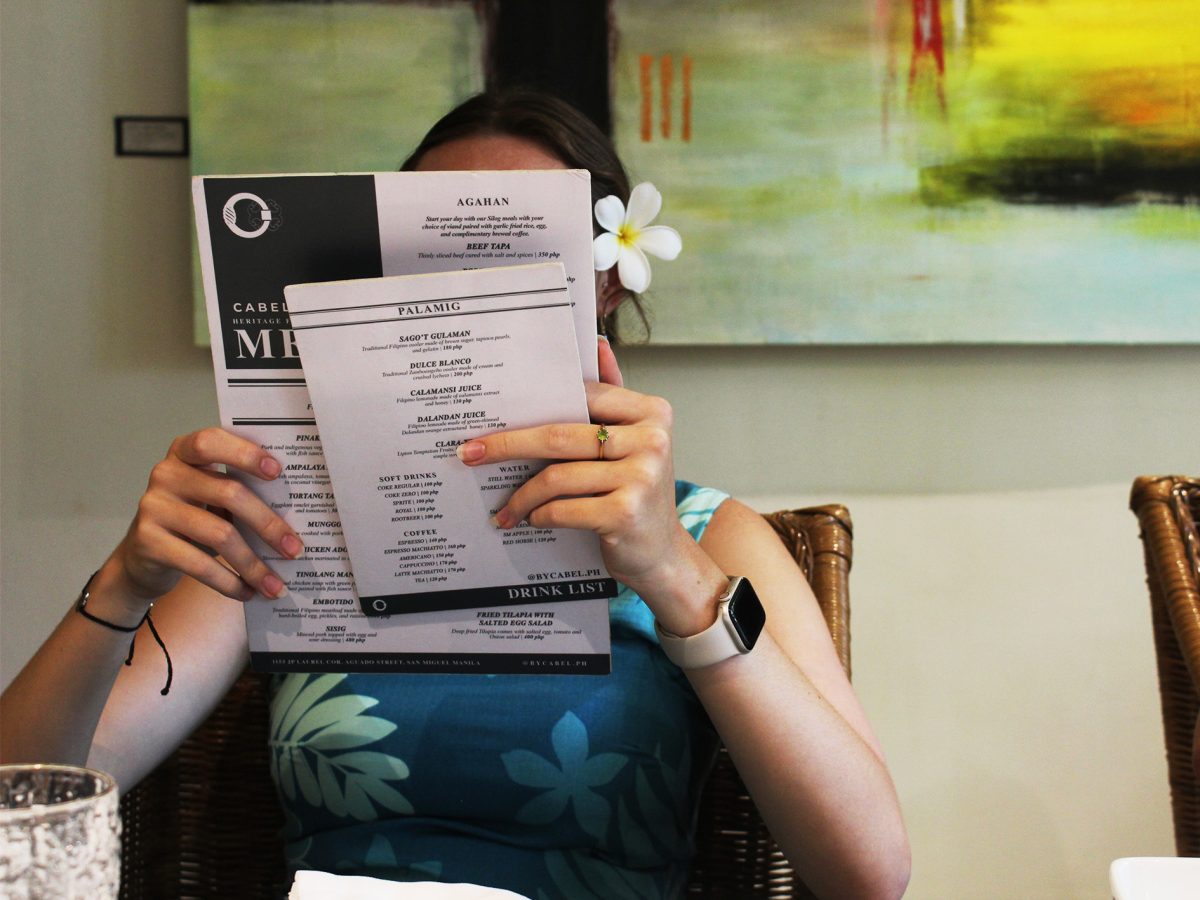

The food, featuring flavors from Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, felt like grandma’s home-cooked meals. The time, care, and effort put into each dish deluged every bite.

“We want to keep it the way that our great great grandparents

did it. It’s traditional. It’s not modern, it’s not futuristic,” Moreno said. “That traditional style emulates throughout our hospitality, our restaurant, and of course our food. I hope that family feeling and the warmth you get through our culture is what you are left with.”