When she started out as an ocean beat reporter for the Los Angeles Times, Rosanna Xia wrote a new article whenever a new study or projection came out about sea level rise.

However, these stories didn’t quite resonate with readers. People would read the article and move on, without any urgency. So Xia changed her approach.

“These numbers and stories weren’t sticking with people, and so I started to realize numbers alone don’t tell the whole story,” Xia explained in a speech at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa on Jan. 16. “People tend to remember these stories. You tell them, not the data, and people tend to remember how they feel rather than the fact that triggered those feelings.”

It was here that Xia realized what to do in her job as a reporter: to create meaning with this data. As a coastal engineer she talked to once said, “We can’t science our way out of this.” Instead, by listening to community voices while looking at the bigger picture problems, it allows people to tell a more cohesive story in a way that is empathetic to their experiences.

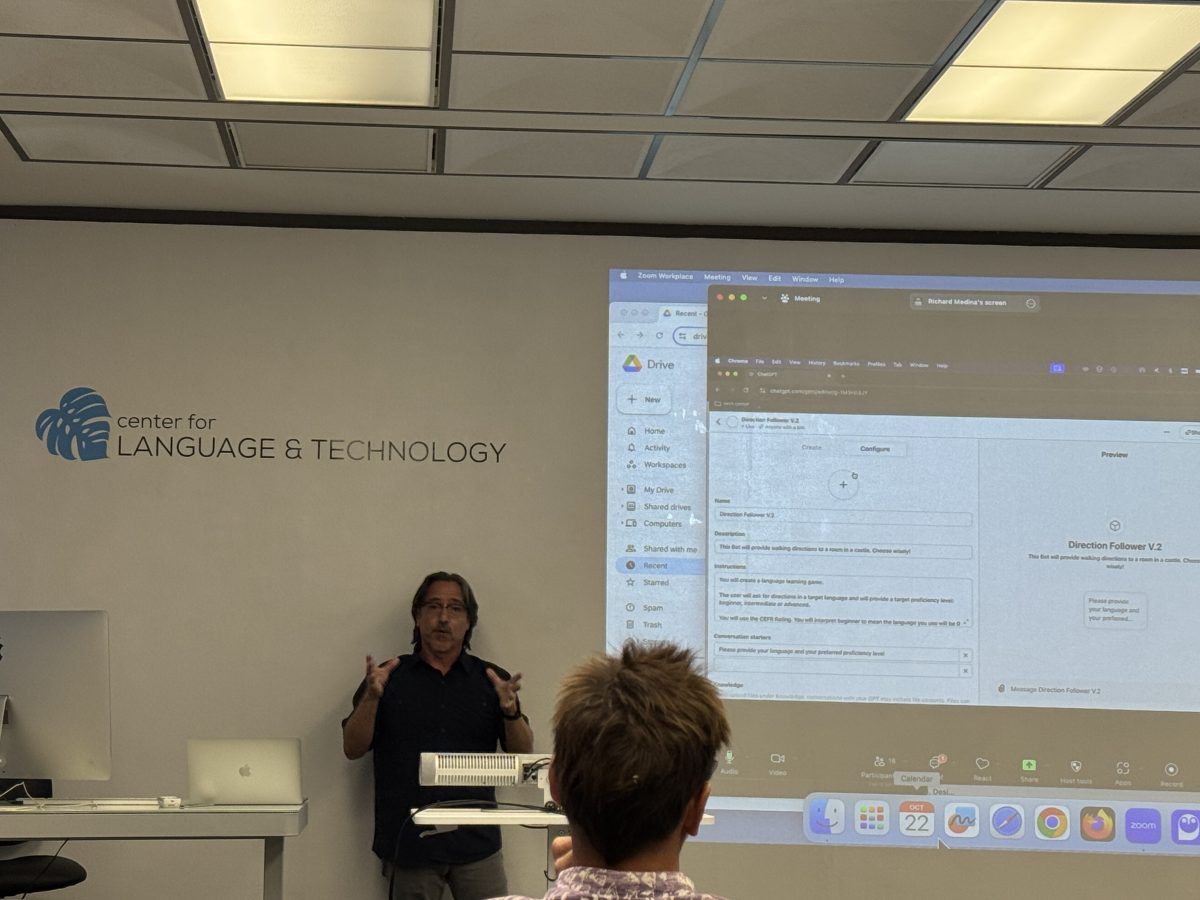

The Pulitzer Prize finalist visited the UH Mānoa campus this past Wednesday and Thursday. When Xia arrived in Oʻahu on Wednesday, she presented an hour-long workshop for journalism students with tips on how to make students’ news writing for their stories more compelling and understandable. Then on Thursday, the reporter spoke as part of the Better Tomorrow Speaker Series (BTSS) on how to best engage in dialogue about environmental issues.

Xia’s visit comes at a vital time for Hawaiʻi: environmentalists are preparing to lobby during this legislative session, affected Californian students and their families are coping with the effects of the recent L.A. wildfires, and sea level rise on the North Shore threatens to sink many beachside homes into the ocean.

Although Xia’s beat as an environmental reporter is based on California’s changing coastlines, her approaches to storytelling apply to other journalistic topics too.

In her workshop with journalism students, Xia coached them on how to improve their writing and reporting to maximize clarity and ease for the reader. Some of the tips she gave include balancing between scene and summary paragraphs, using more sensory details outside of sight, and giving the reader “easy wins” through fun facts.

The reporter advised bouncing off meanings with experts on words and concepts that would be difficult to understand with heavy jargon. For example, a person could tell what a stink bug smells like when they step on one, but someone without that experience may not be able to get a sense of how exactly it smells. So when interviewing experts, the reporter and expert can throw ideas and questions to create a more familiar description. From here, the reader is able to get an easier idea of what a stink bug smells like.

On a similar thread, these back-and-forth discussions to create clearer meanings can also apply when journalists ask questions to and from people that may have more similarities than perceived differences. These similarities can then transcend beyond social, geographical, and political barriers.

“I think the more that we’re able to connect all of the dots, because climate change is connected to everything, the more I think we’ll be able to have deeper conversations,” said Xia.

Xia explained in her talk that serving as a connective tissue between communities takes understanding what people care about: it takes empathy, bringing people out of their corners, assessing what people find valuable, and framing an impactful story. In short, constructing bridges of information that allow people with different priorities and expertises – lived experiences or research – to come together and collaborate on the next step forward.

“I really try to make sure that my conversations with people donʻt feel transactional,” said Xia. “Thereʻs no trust or relationship building there. And so, I think the more we can as journalists recognize that we are part of the community building and just stitching together this universe of so many people doing so many great things.”

It’s this type of radical listening that is sorely needed in this cutthroat culture filled with fatigue, cynicism, and widespread divides.

“[Xia’s] an expert in communicating science and policy to a larger audience,” said Robert Perkinson, the Better Tomorrow Speaker Series coordinator. “I think that was especially valuable during her extensive conversations with UH researchers, community advocates, and policymakers. She’s thought a lot about how to communicate crisis in such a way that inspires action rather than despair.”