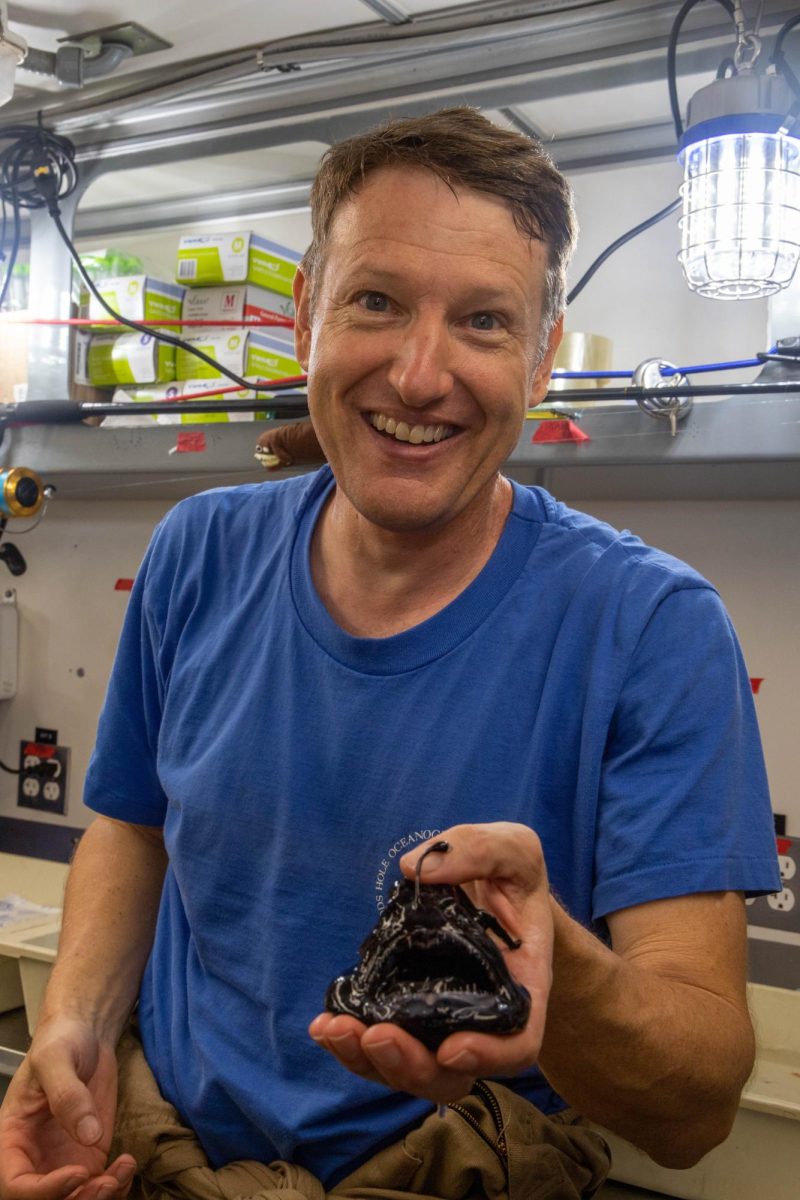

A Hawai’i law passed last year to prohibit deep sea mining in state-owned waters has one major defect, according to Jeff Drazen, an oceanography professor at UH Mānoa.

The Hawai’i Seabed Mining Prevention Act prevents mining within three miles of the islands’ shores, but Drazen said those areas are unlikely to be of interest to the emerging industry.

“Deep sea mining is going to occur largely far offshore,” said Drazen. “(This bill) is largely symbolic.”

Drazen is raising awareness about deep sea mining, its risks and why we should be aware.

“Current mining companies are proposing to drive house size tractors across the sea floor, scooping up poly metallic nodules, shooting them up a pipe to a surface ship, discharging unwanted mud back into the water column,” said Drazen.

The mining industry is focused on gathering metals needed for infrastructure linked to renewable energy, including electric vehicle batteries. But various environmental concerns are being raised, including biodiversity loss, seafood contamination and impacts on the relationship between the ocean, carbon dioxide, and the atmosphere.

Pete Stauffer, the ocean protections manager for the Surfrider Foundation, calls the law “a good start.”

“What the state did was more of a proactive step, so it permanently protects Hawaiʻi state waters, which are important ecologically, and it also contributes to a global pushback and concern about potential seabed mining in international waters,” Stauffer said.

As for why deep sea mining is needed, The Metals Company website states that it would alleviate the pressure placed on the world’s ecosystems due to the demand for metals. The Metals Company did not respond to a request for an interview.

“We feel it is important to supplement metals supplies in a way that inflicts the least impact on the planet and people,” the company’s site stated. “This means giving fragile rainforest ecosystems a break, and increasing the supply of high-quality metals which can be recycled and reused without breaking down.”

While commercial mining has yet to take place, there are rising concerns about its impacts from researchers and ocean advocacy organizations.

According to an article by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the International Seabed Authority has spent a considerable amount of time negotiating frameworks, but gaps remain.

The article states, “These gaps include fundamental issues, such as lack of agreement on environmental baseline data requirements; what constitutes permissible environmental harm; compliance, monitoring and enforcement mechanisms; how to address underwater cultural heritage; and insurance and liability requirements.”

Stauffer says that most groups, Surfrider included, are advocating for a moratorium on deep sea mining until a regulatory framework is implemented.

“I think the main concern now is that there is no type of regulatory process or environmental review, let alone enforcement mechanisms to address it,” said Stauffer. “The main interest is to engage with the ISA to create a regulatory framework able to evaluate environmental impacts and have standards for how it might be done.”

As there is no way to pursue this mining without environmental impact, discussions tied to minimization are taking place.

“There are other companies that are talking about going down there in a very direct way, picking individual nodules off of the sea floor and then returning them within a robotic vehicle to the surface ship,” said Drazen. “There’s no big pipe and you’re not bringing a lot of mud with the nodules.”

While this method would reduce impact, it will still take for the environment more than a lifetime to recover.

“The nodules are essential habitat for organisms, and they take millions of years to grow,” said Drazen. “So if you remove them, you permanently remove that habitat.”